What will it take for smallholder farmers to transition to low-emissions agriculture?

Santosh owns a small two hectare plot of land, roughly half the size of the London Eye, in Northern India. He is a second-generation farmer and agriculture is his only source of income. Things aren’t the same as they were when he started working in his fields two decades ago.

Santosh can no longer predict monsoons with the relative accuracy he was famous for, and prepare his crops for pre-sowing. Irrigating his rice fields has been challenging with access to natural water sources dwindling and the water table decreasing. Extended periods of drought affect his ability to time the harvest of his rice crop, and plan for the next cropping season, let alone leave the lands fallow. Giving the land time to breathe was something his father strongly recommended. The number of considerations only continues to increase and it preoccupies Santosh’s days and weeks. He heard from a local agronomy expert that his problems aren’t just his. And that ‘climate change’ has been affecting smallholder farmers across the country.

Santosh represents nearly 85% of all agriculturists in India.

India's Agricultural Landscape

India is primarily an agrarian country, with agriculture contributing to nearly 18% of GDP, and engaging 54.6% of the country’s total workforce. Agriculture in India has historically provided its people with food security and been a key driver of the country’s growth. Government policies and allied activities continued to promote increased yields through industrial agricultural activities and resource-intensive techniques.

The trade-offs only became clear recently. The agricultural sector has contributed to approximately 20% of total GHG emissions, or around 400 million tonnes of CO2e annually.

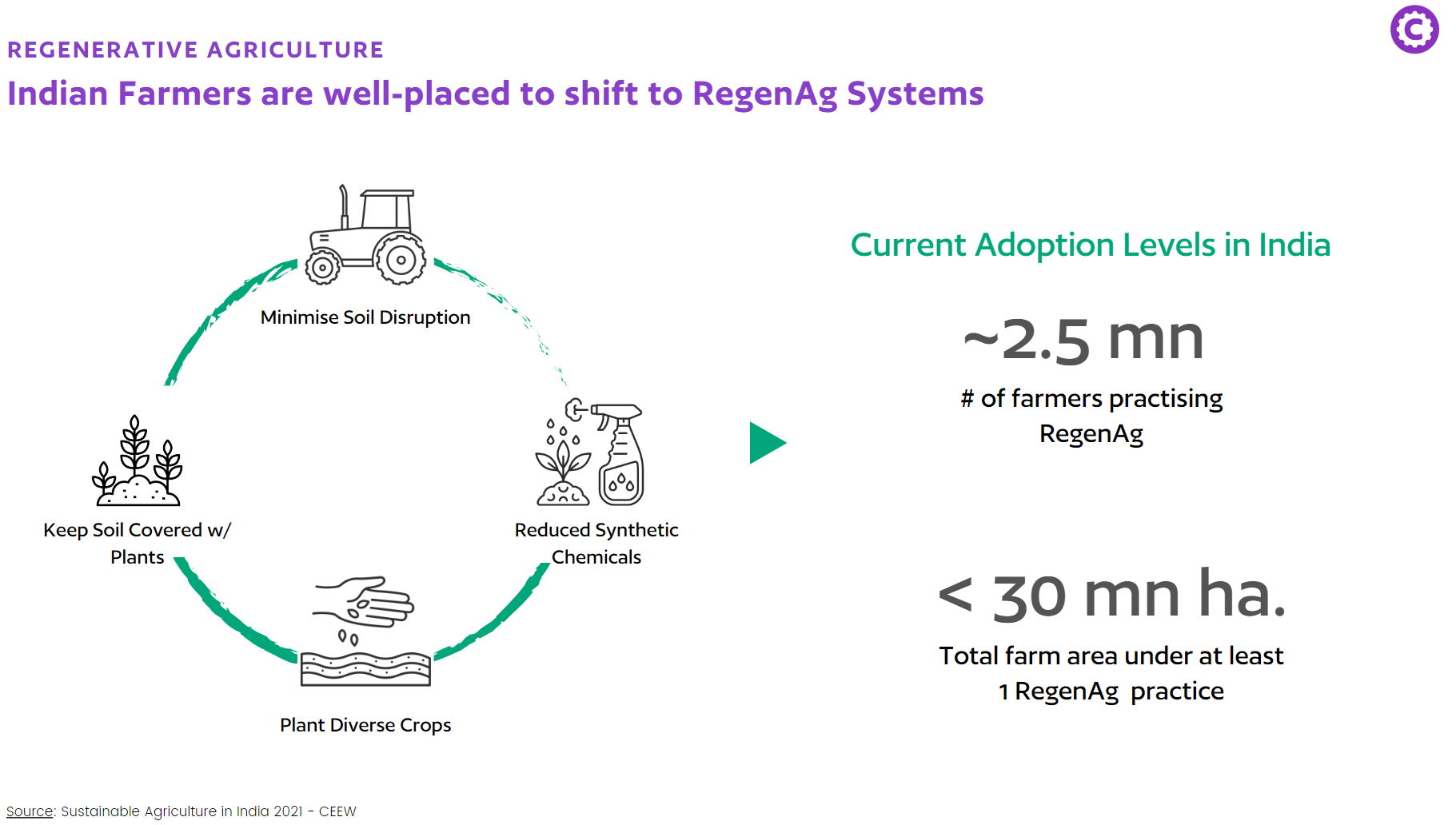

The majority of farmers in India, like Santosh, are among the poorest in the country. This leaves them no choice but to stick to traditional farming practices which have a higher environmental footprint. Coupled with a lack of effective mitigation measures and adaptation technologies - smallholder farmers bear the brunt of the worst effects of climate change.

However, there is a promising pathway out of this.

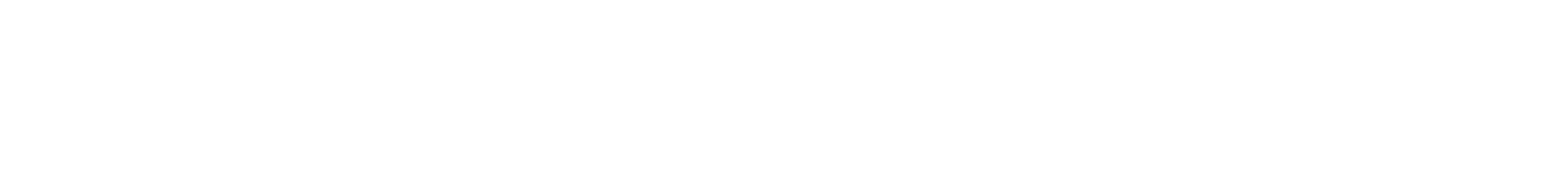

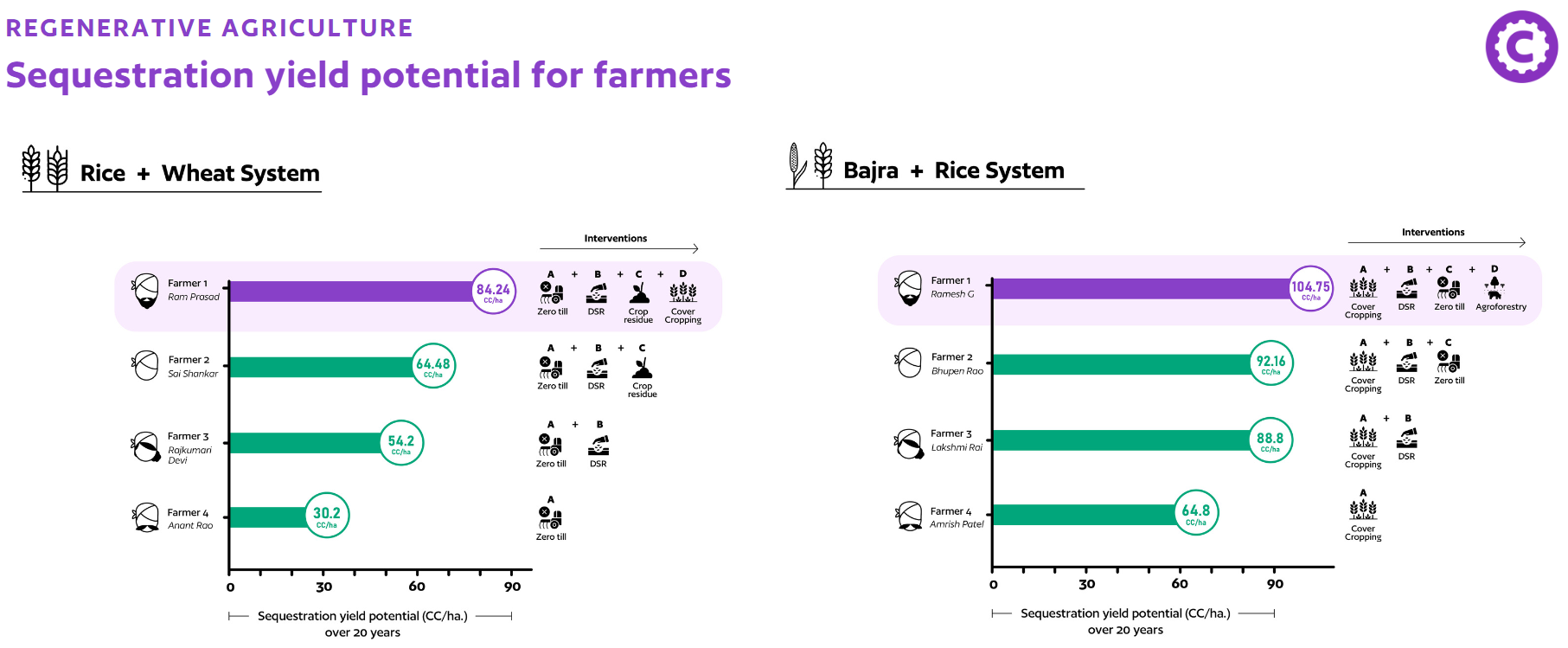

Regenerative agriculture has the potential to both improve the livelihoods of India’s farmers and reduce the sector’s carbon emissions. It improves soil health through practices that increase soil organic matter, improve crop yield, reduce input costs and enhance resilience to climate change. Nevertheless, the switch to regenerative agriculture is not simple. Many smallholder farmers reside in rural areas with limited access to education, training and resources. These conditions present practical constraints to adopting regenerative agriculture. The most significant of which is the lack of mechanisms that provide smallholder farmers a financial cushion to gradually transition towards low-emissions agriculture.

Carbon credits as a meaningful path forward

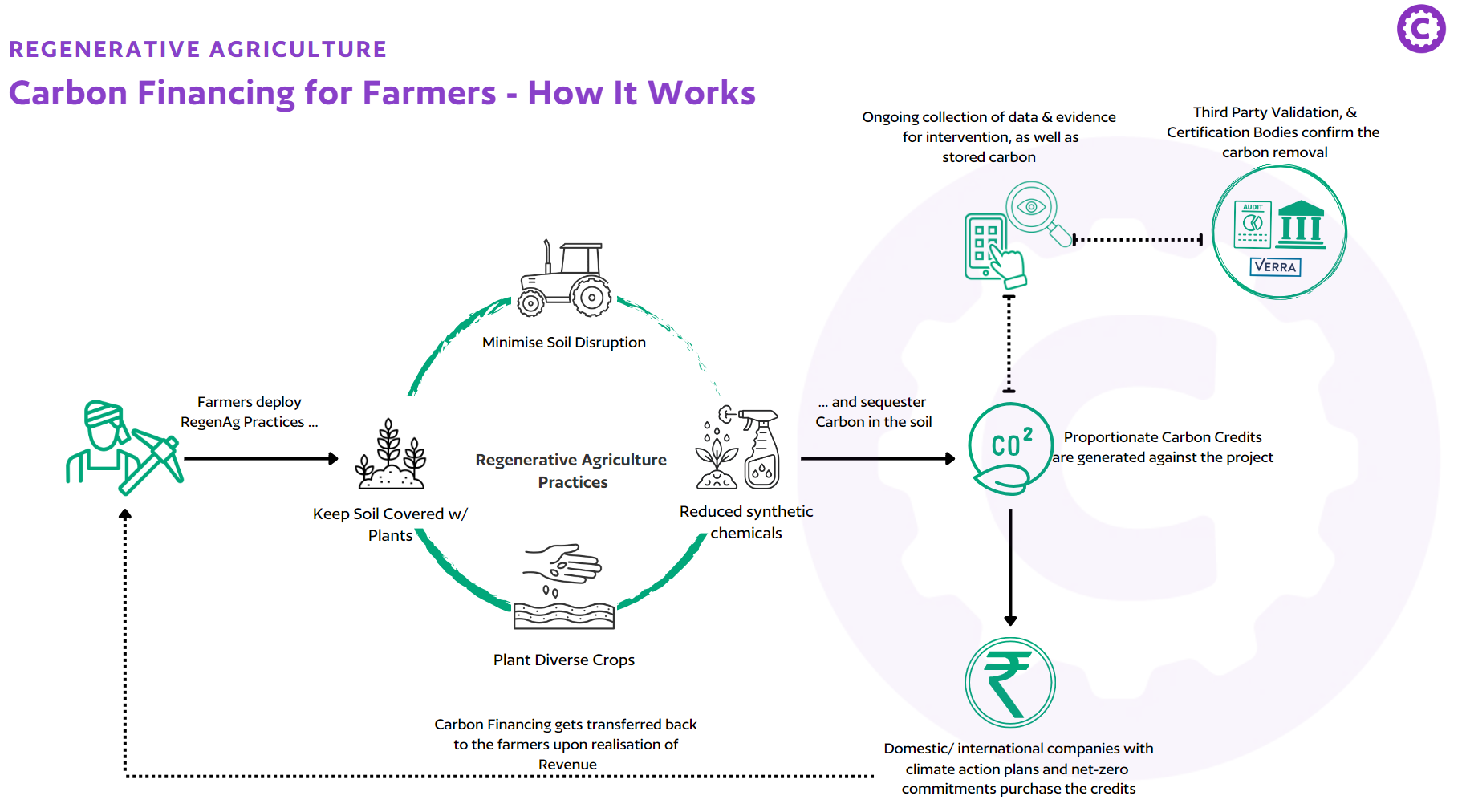

This is where Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM) and carbon credits can play a critical role. They provide market-based mechanisms for remunerating climate action and incentivising sustainable farming practices. Agroforestry, cover cropping, and conservation tillage, have the potential to sequester carbon in the soil and biomass. By implementing these practices, farmers can generate carbon credits based on the amount of CO2e they sequester. These credits can then be sold in voluntary carbon markets to companies or individuals looking to offset their emissions. It is a game-changing solution, in theory. In practice, the local realities of developing markets, like fragmented landholding and minimal technological orientation, mean this transition cannot occur without large-scale external financing.

Unfortunately, a regenerative agriculture project in the Indian context is not conventionally considered to be a financially viable investment. The risk-return profile does not whet the appetite of conventional financiers. There are sufficient uncertainties in the early years of a carbon farming project that will deter investors that seek returns at market rates. Accurate measurement of the carbon sequestration which leads to a commensurate issuance of carbon credits requires robust monitoring systems and is operationally intensive. All these factors combined mean the commercial capital necessary for these projects to succeed remains out of reach.

It is important to qualify that these challenges are not unique to regenerative agriculture projects alone. Much of the climate sector in general is characterised by uncertainties, high risks, foggy rewards and limited return assurance. Long-term forestry projects or wildlife conservation projects find it equally difficult to secure financing, particularly from private sources of capital.

Specifically in agricultural lending, market rates are often too high given the opportunity cost of lending to smallholder farmers and the high risks involved. Terms offered are often untenable without sufficient buffers or protection mechanisms, and do not account for the transition costs towards climate-smart agriculture or the cyclical risks that come with rapidly changing climate.

Innovation comes at a cost, and it is often borne by institutions who have the vision and wherewithal to catalyse financing early. In doing so, they create the right environment for innovative, high-impact solutions to achieve market readiness and widespread adoption subsequently. This more efficient approach to financial deployment ensures that important climate projects in developing markets can attract critical capital at the scale they need to create real impact.

Blended Finance can fuel the growth of RegenAg.

Blended finance refers to the strategic deployment of concessionary capital to de-risk climate projects so that they become attractive for commercial capital investments. In the case of regenerative agriculture, concessionary capital improves the risk-reward ratio for banks and private investors. Introducing concessionary capital at the early stages of a carbon farming project can help bring down the overall cost of capital, absorb initial risk, provide the much required technical skills, and instil confidence in investors and financial institutions. In doing so, it paves the way for pioneering investments that would otherwise have been held up on strictly commercial terms.

Incentivising smallholder farmers to shift to low-emissions agriculture through the generation and sale of carbon credits perfectly aligns with the three key components of a blended finance proposition ~

- Out-sized development impact across environmental, social, and economic parameters

- Strong rationale for concessionality given the risk-return profile in the early stages

- Clear case for additionality, given the inherent viability within the project, once de-risked, and the revenue potential to absorb commercial capital past the early stages

In conclusion, the potential for catalysing climate action through blended finance is immense. An initial influx of concessionary capital will help in the system-level transitions to low-emissions agriculture in the following ways:

- Provide the necessary investments for technical assistance and equipment costs for smallholder farmers to make the switch to climate-smart agriculture

- Reduce distortions in project economics and ensuring durable financial incentives for smallholder farmers is built into the project design

- De-risk the project’s early uncertainties and directly contribute to achieving predictability in project cash flows, around Year 3, via the generation and sale of carbon credits.

- Improve the overall viability of the project and prime it to absorb scaling capital from commercial investors, who can be serviced through recurring and predictable cash flows

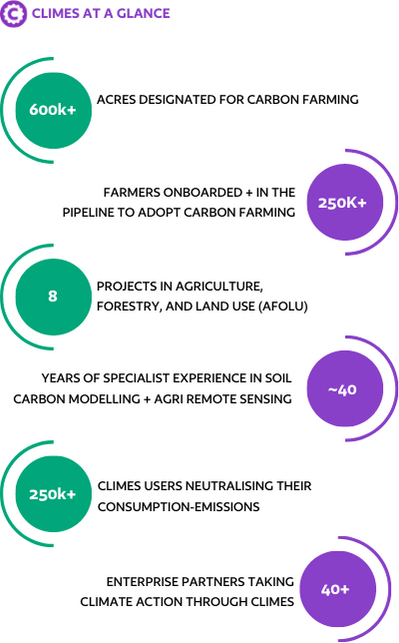

Climes is a climate-finance company that is building the infrastructure for designated as well as non-designated climate capital to flow to high-quality climate action on the ground. Our approach is rooted in enabling the transition towards low-emissions agriculture through large-scale implementation partners with strong working relationships, science-based Digital-MRV solutions, and program structures which keep smallholder farmers at the centre of the finance flow.

Our current portfolio and pipeline of farmers extends to nearly 250k smallholder farmers in ~ 600k acres of land.

Get in touch with us to know more about our deliberate approach to incentivising smallholder farmers and to explore potential collaborations.